Bartholomae, David. “Inventing the University.” When a Writer Can’t Write: Studies in Writer’s Block and Other Composing Process Problems. Ed. Mike Rose. New York: Guilford, 1985. 134-65.

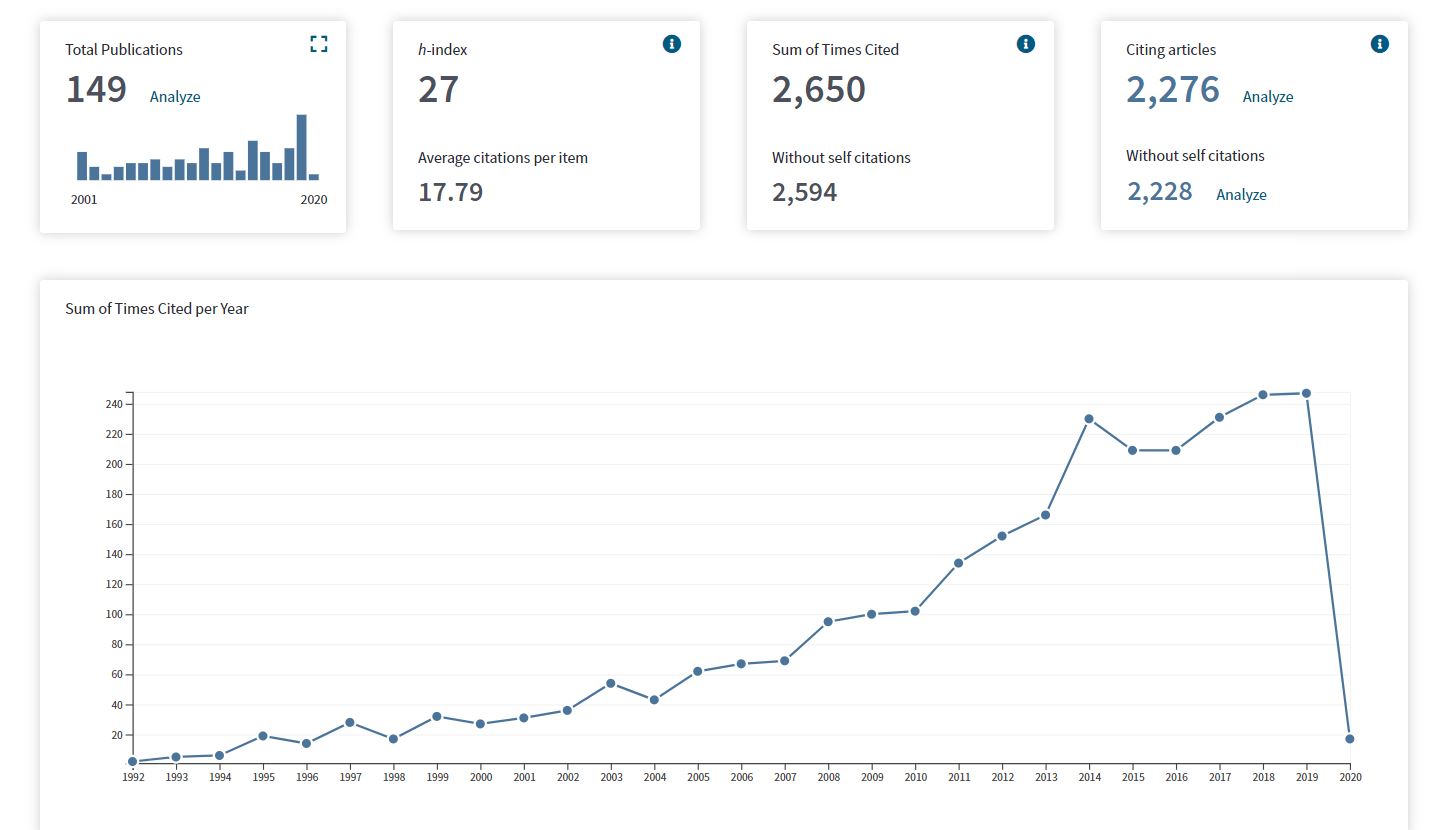

What can you learn about the number of citations to this article per year since it was published? As is evidenced in the graph the number of times this article is reference shoots up in the early 2010’s and remains popular through the 20-teens. While it’s popularity seems to be waning in the last few years it is much more cited than in the 10 years initially after its publication. I posit this is because the field of rhetoric and composition has come into itself in the past years. There has been more interest in defining the boundaries of the field and perhaps seminal pieces like this help with that work.

What can you learn about who cites this article? What are their disciplinary identifications? The majority are from English, composition, writing, or rhetoric. However I am seeing linguistics, TSOL (quite a few L2 publications actually), and education scholars as well. I see a few from library science too. The big hitters tend to be College English publications and other NCTE publications associated with writing studies.

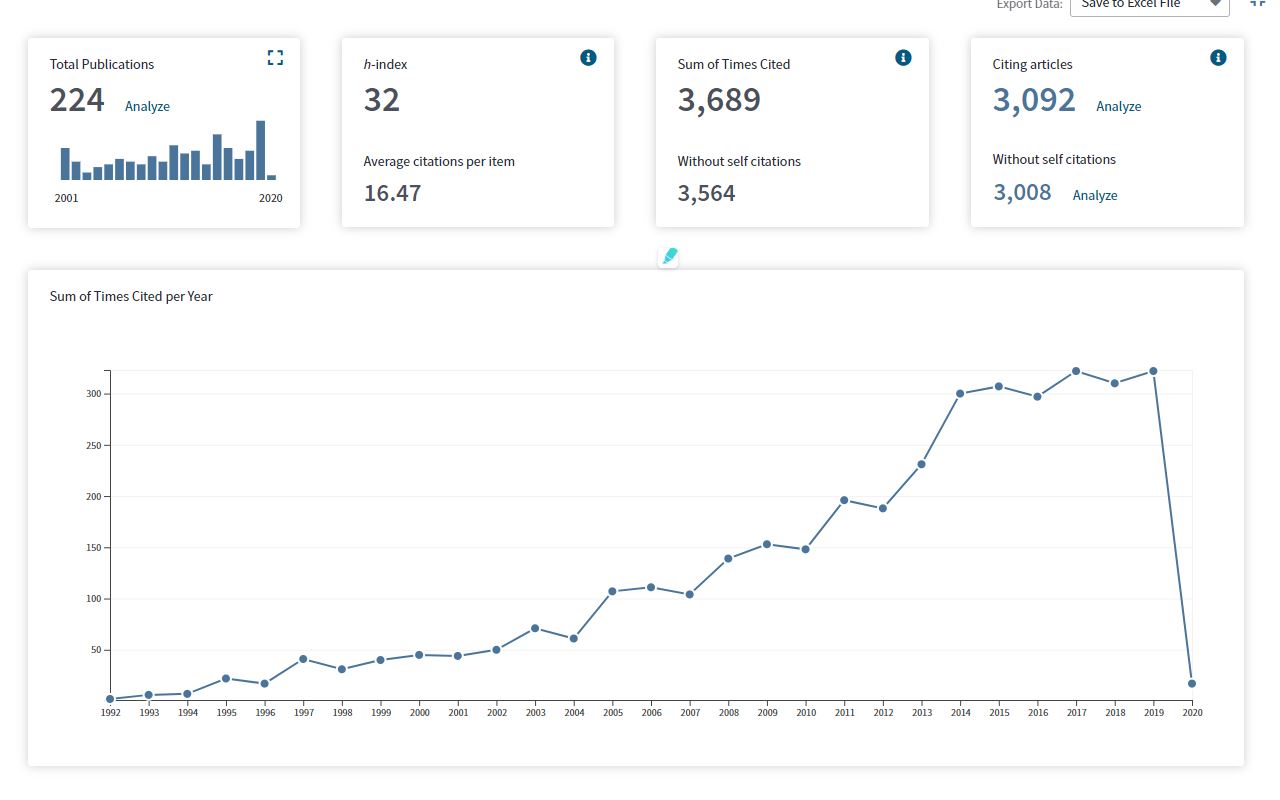

Which of these numbers would you prefer to have used in evaluations for hiring and tenure? Why? I think I’d prefer to have the second number because it provides a more holistic view of a body of research and a trajectory of academic communication than just one article does. It is very interesting, however, to note that it took quite a while for this to spike. Could it be because of digitization and access to the information? Or, did it take that long for folks to find Bartholomae’s work important? I don’t know. Tenure usually takes 6-10 years, though, and if Bartholomae were assessed by his initial numbers, he would not look nearly as impressive as he does now. Just thinking about the tenure process itself as problematic when considering “impact” and the like.

Is this kind of analysis appropriate for all academic fields? Why or why not? I think this is complicated. While metrics are needed for promotion decisions, these metrics only show who is citing your work. There is bias in citations. There have been historical issues of people of color, for example, being under-cited. Women, too are cited less than men. Finally, I wonder how things like creative projects, DH projects, or other un-traditionally published kinds of scholarship can be accounted for here. In my field the journal Kairos is an example of this non-traditional kind of scholarly work. I see that some of our readings deal with this for the week, so I look forward to seeing what they say about digital humanities and bibliometrics.

A final question I have–and I should know the answer to this given my library background–is how does this compare or contrast to the citation search in Google Scholar? The numbers for Bartholomae were different than in Web of Science so what is being indexed in each? Insofar as I’m aware WoS veers more social science and hard science, no? Does this affect the number (it clearly does) and what does that say about us relying on such numbers? Especially for humanists? Furthermore, for outward facing humanities or scholarship that might be reported in non-academic settings, how does that fit into the mix? Being cited by journalists, for example, is a feat in-and-of itself, but it would not show up in these kinds of bibliometric ratings.

sdaiker

February 9, 2020 — 11:40 pm

I also noticed that the Web of Science has more of an emphasis on hard science and social science than the humanities. I tried searching for “Schrader, J” using the Basic Search, and of the one hundred Web of Science Categories that the search results were sorted into, only two stood out to me as non-STEM fields (“history” and “humanities multidisciplinary”).

As you suggested, I am also concerned about the ways in which tools such as the Web of Science do or do not accommodate non-academic citations, or even academic citations in formats other than journal articles, as seems to be the case with the Web of Science.