1. World Historical Gazetteer

For this task, I chose to search for “London,” because I thought that this place name would generate results drawn from several of the World Historical Gazetteer’s datasets and results that refer to physical spaces other than London, England.

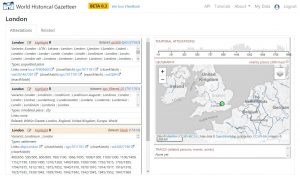

“London” generated 90 search results, with the first result, “London (inhabited places) [GB],” referring to what could be described as the physical space of London, England.

This result has four attestations drawn from three datasets (geonames cities (500), Getty TGN (partial), and DK Atlas of World History), and the attestations varyingly classify London as a populated place, inhabited place, city, and settlement—which I thought would be the case, given the temporal span of “London” (or “Londinium”) as a place.

I was also interested in the geographic span of “London,” in the sense that this place name or variations of it might refer to physical spaces other than London, England, given our readings and our discussion of gazetteers as providing data about the past through historical places linked by name and temporal and spatial relationships.

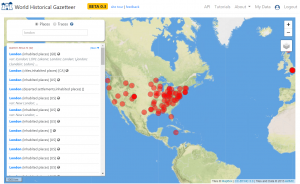

This image (above) shows the geographic span of search results for “London,” with a more opaque circle indicating London, England’s physical space and a dense cluster of circles representing instances of “London” as a place name in the United States and the Caribbean.

I was interested here in the map’s visualization of search results reflecting colonial relationships, as seen in the cluster of results in the northeastern part of the United States and in Little London, a community in Jamaica. The map also visualizes what might be thought of as aspirational relationships, in the sense that America, to some extent, modeled itself as a group of colonies and as a young nation on Britain (and France), which might be reflected in place names.

2. Recogito

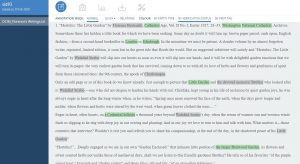

For this task, I selected a group of four short texts from 1927–1928 from my current research on Washington National Cathedral. Each of the texts are concerned with establishing a relationship between the cathedral and the “Old World” through various materials brought to the cathedral.

As a tool, Recogito was most useful for me in that annotating texts highlights places and people of interest and visualizes how frequently they are mentioned in the text. With the group of texts I selected, at least, it seems that annotating would require a human user with some familiarity with the text and the people and places to which it refers. In addition to instances in which places and people are named specifically, there are instances in which phrases and terms are used to refer to previously identified locations and individuals: “the devoted monastic brother,” the “Little Garden,” the “Cathedral,” etc. The person creating the annotations would need to be familiar with the people and places mentioned in the text, or at least be able to make educated inferences, in order to annotate such references.

In our readings, our discussion of gazetteers, and our tasks with the World Historical Gazetteer and Recogito, I was interested particularly in notions of space and place, in which “space” refers to a coordinate location or spatial situation and “place” refers to a site of human, historical experience. These concepts relate to my research interests and my current work on the use of material to establish connections between “there” and “here” and “past” and “present,” and the subjective use and interpretation of these ways of understanding the world in spatial, or “platial,” and temporal terms.

I’m looking forward to reading other students’ blog posts and to our discussion on Tuesday, in which I would be interested to talk about to what extent the World Historical Gazetteer and Recogito as visualization tools enable us, as individual researchers and in our fields, to think about our material in different ways.