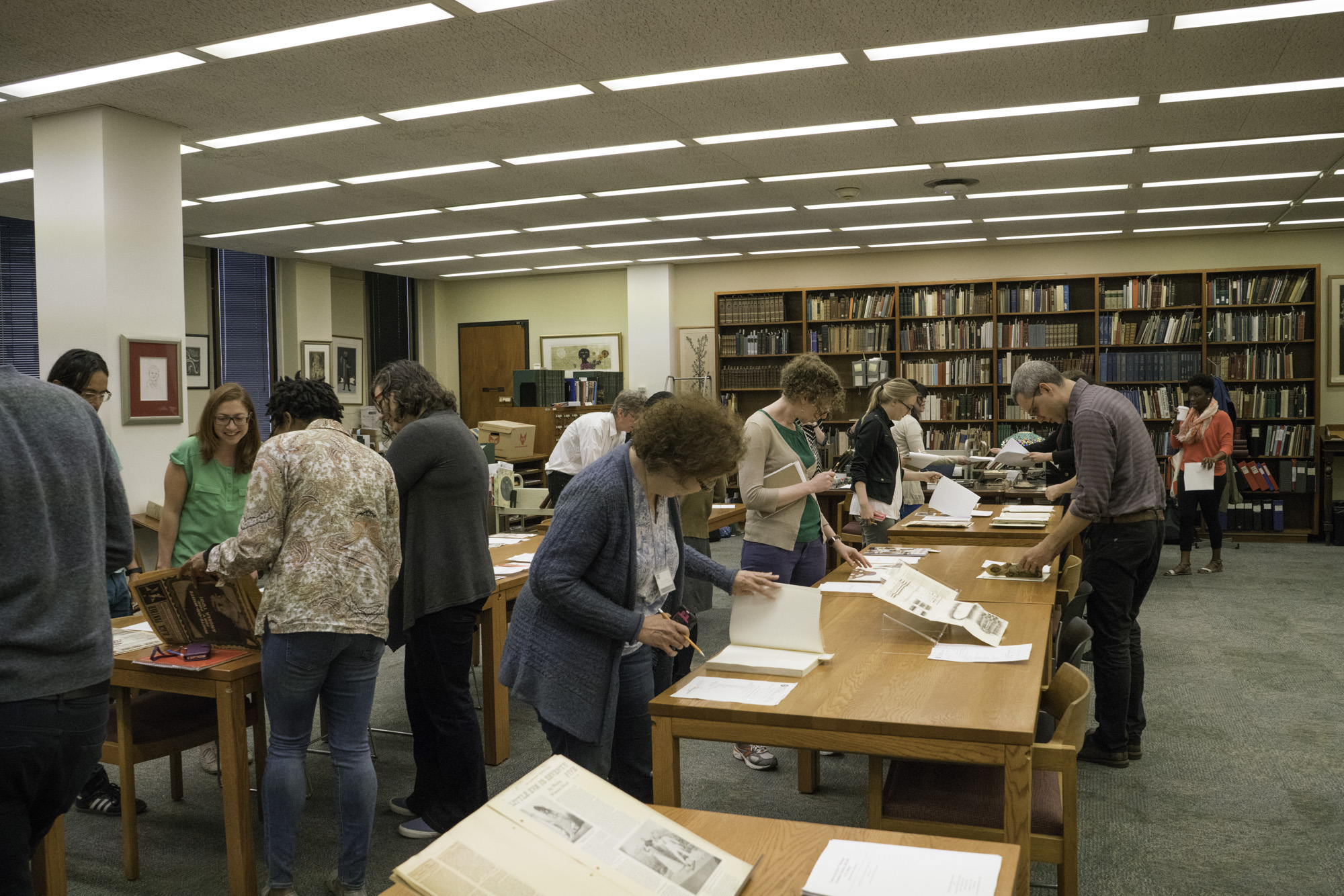

Our workshop ended on Friday the 13th with a beautiful day at the Carnegie Library of Braddock with the artist collective Transformazium, after a packed week of field work and intense conversation with an amazing group of graduate students and faculty from across Pitt's campus.

Over the course of the week we met and talked with various curators, educators, and archivists at the Carnegie Museum of Art, the Teenie Harris Archive, the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, the Heinz History Center, the Allegheny City Gallery on the Northside, Pitt’s special collections and multiple archives, and the Art Lending Library in Braddock. We interacted in various ways with objects on display and brought from storage, as well as curated selections of mixed materials from larger collections, and on the last day had a chance to do some speed-curating of our own in the art lending space at the Braddock Library. In between, we talked a lot about what we had seen and heard and about what we should do to put ideas in practice and push the conversation forward in public.

For me personally it was a revelation to move from one radically different collection to another and to ponder the structural differences that help determine their narratives, audiences, and engagements. Each institution has its own criteria of quality and value. These value systems in turn create communities around them. Some systems are inherently more exclusive than others and therefore present particular challenges for an ethic of inclusion.

At the Hunt Institute, for example, with the help of their generous staff we spent a couple of hours examining prints and books mostly against the grain: we looked through botany books and various records of collecting expeditions by European and Anglo colonizers to see how they represented the indigenous and enslaved peoples who actually supplied much of the knowledge. Against the hierarchy of power and knowledge communicated by the materials themselves, we worked to recover the devalued voice and expertise of the peoples at the bottom of the hierarchy. At the Teenie Harris Archive, in the Carnegie Museum of Art, with the help of their equally generous curators, we had the privilege of entering a lost world – the largely African American Hill district before the destruction wrought by urban renewal – through the eye and lens of the maker himself, a man who did not self-identify as an artist and who rarely entered the art museum where his huge collection eventually found a home. Here the institution has the good fortune to mine the knowledge of the community, because many of them from those days are still alive and come in to talk about their pictures and their world. And so an archive of images has also become an archive of oral memory and of written history, all deeply interwoven into a still living community fabric. A quote my co-facilitator Shirin read to us two days later keeps returning to my mind: If one no longer has land, but has memory of land, then one can make a map.

And in Braddock, where Shirin read that passage – one of the poorest municipalities in our region – we thought about the value system of an art lending library in the context of a community whose resources, knowledge, and creativity tend to be ignored in a racialized master narrative of blight and distress. Here is a public library that lends original art for three weeks to anyone with a county library card – art that includes work donated by every artist represented in the 2013 Carnegie International, black arts printmakers, emerging artists, and paintings by incarcerated men in a prison art program. All of it surrounded by books on art and society in a light-filled room with salaried art and culture facilitators from the nearby community to discuss the art and its makers and stories. From these artworks and books we curated our own multi-media displays on various themes which had emerged here and there in our week-long conversation.

That conversation was simultaneously challenging, contentious, draining, and energizing. But the big question we returned to all week was what can we do? In response to this challenge several different concrete projects have emerged which you can find in the Projects tab of this website. And below, to give you some idea of the texture of our workshop week, we include some of the participants’ reflections on images that document our encounters.

Kirk Savage

Day 1 of the workshop, in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, we stop to hear a very smart Pitt undergraduate describe her senior thesis research on the “Arab Courier Attacked by Lions,” a 19th-century French diorama originally shown in Paris at a world’s fair. It’s an Orientalist fantasy complete with fake blood and real human teeth that has been masquerading for over a century as a scientific display. Now the new director of Natural History plans to move it into the passageway between the art and natural history museums. Aaron’s oblique shot through the glass is a beautiful way into the strangeness of this object and our moment of encountering it. It seems to float between worlds and between times: what is its “now”? 1867 when it was first conjured, or 1898 when the museum acquired it as an anthropological specimen, or 2016 when the museum decides to relocate and reinterpret it? In a post-9/11 world, with its ongoing spiral of terrorism and American military intervention spreading its human toll mostly in Muslim countries, how does this violent relic speak to us in Pittsburgh of all places? How can we decolonize its elusive but ever-popular mash-up of old and new colonialist dreams and ethnographic stereotypes?

Dominique Johnson

In an early conversation with representatives from the Carnegie Museum of Art, we were asked to comment on ways to engage underrepresented communities as regular visitors beyond targeted, featured art exhibits. After hearing about various programs that provide temporary memberships to approved school programs and organizations, namely one that catered to young girls of color, the museum staff noted a general discomfort in the lack of adequate programming to address their concern. For them, the draw of the museum should be inherent to the space. They discussed the difficulty of relating the value of such an experience to people whose experiences in similar spaces may have been negative, largely due to issues of accessibility, race, class, and education. What followed was a fruitful discussion that engaged topics such as managing microaggressions, alternative outreach methods, and the creation of specific docent-led tracks to accommodate those who may be less familiar with art spaces in general. We left the conversation wondering: Who are art museums for? What is the intended general audience of CMOA, in particular? How can such a space be better integrated into Pittsburgh’s diverse communities? What is the role of the Carnegie Museums in terms of documenting and engaging the local and regional communities within which they are situated? While we reached no easy solutions, this conversation shaped the rest of our week.

Photograph by Kirk Savage

Shirin Fozi

Maria Sibylla Merian was living in the Dutch colony of Suriname in 1700, recording plants and insects in paintings that would be published five years later in a ground-breaking study. It was a special treat to examine a rare early edition of this book at the Hunt Botanical Institute, because Merian was a gifted scientific illustrator and also a rare professional woman artist from early eighteenth-century Europe. Her palpable respect for the indigenous people of Suriname has long been noted, along with her criticism of the treatment of black slaves on Dutch plantations. These attitudes are quietly embedded in the text of her book, which includes acknowledgements of the women of color whose insights made Merian’s work possible.

Marina Tyquiengco

On Day 5 of the workshop, we visited Transformazium Art Lending Library at the Carnegie Library of Braddock and toured the library as well. The photograph shows us engaging in group discussion after using the art lending library to create small exhibits/groups of similarly themed objects. This demonstrates the possibilities that an art lending library can have, namely decentering the role of the curator and more generally the museum by allowing library members to have unique experiences with works of art and form their own connections between pieces. The suggestion to work in groups fit the collaborative nature of the Transformazium artist collective and highlighted different interests of the workshop participants, who came from a variety of backgrounds. We were aided in our curatorial efforts by Mary, one of two art ambassadors whose sole role is to help library members check out works of art. This emphasized the impact that projects like Transformazium can have, engaging with the local community and getting support from local government and nonprofits to create jobs. The visit to Transformazium was, for me, a finale of the program, seeing artists engaging directly with a community that has not historically had a lot of access to the arts. Can this kind of community engagement only come from a long sustained effort? Is the Transformazium with its many moving parts an achievable model for expanding access to arts within communities? How can we engage with the fact that the project was initiated by artists from New York City who are white and middle class? Does it matter?

Gretchen Bender

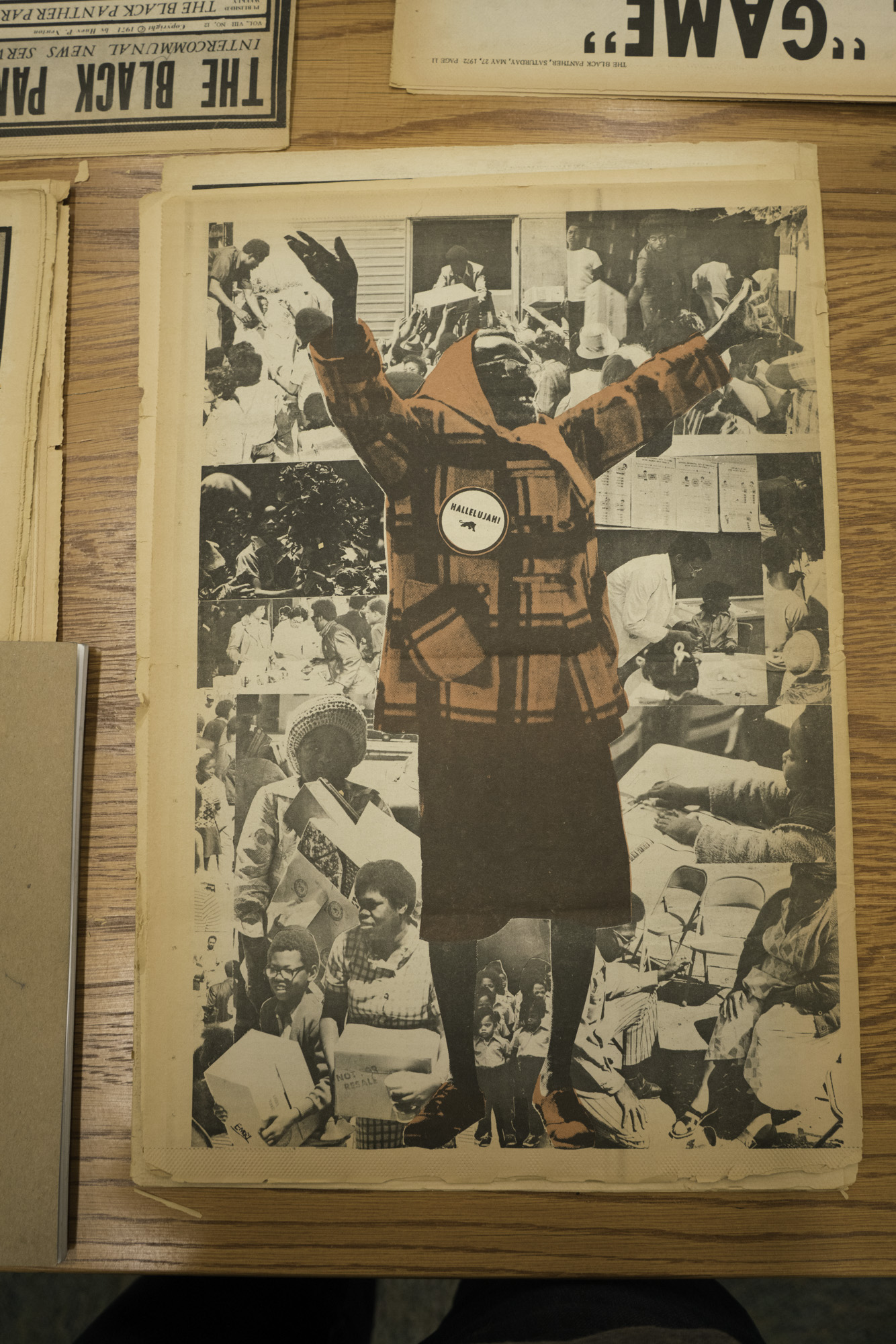

Arrayed on the long tables of the Special Collections reading room, The Black Panther newspapers were suspended between resolute presence and fragility. Their graphic power drew our attention. Bold, stark headlines were girded by collaged juxtapositions of photographs that gave a face and immediacy to the journal’s feature story. Black and white text and image were accented by strong red, or warm yellow or sonorous blue.

Each edition of The Black Panther includes a full page artwork on its back cover, the ‘last word’ given over to the voice and power of visual imagery to make a claim. Next spring, I will be working with a team of undergraduate students to study these art works, learning more about the artists and designers who made them, the editorial thinking that shaped their appearance in the journal, and their connection to featured stories. How might these artworks be catalogued so future researchers and scholars can access particular images? In particular, how might I incorporate these artworks into our core auditorium class, Introduction to World Art? How might students work with these original documents in person?

As we visited the journals that were displayed for us, we were encouraged to linger, to turn pages slowly and take in headlines, text and pictures. With sadness and frustration, we commented on how little had changed in the years since the newspapers’ publication and our present. Essays feature high incarceration rates for young Black men, substandard educational resources for schools, poor housing options and the stark realities of gun violence on city streets. As we turned the yellowed and brittle pages, pieces of newsprint crumbled onto the table. The historical artifacts revealed their age but also their vital connection to the world we still inhabit.

Caitlin Bruce

“Curation as Re-Activation”

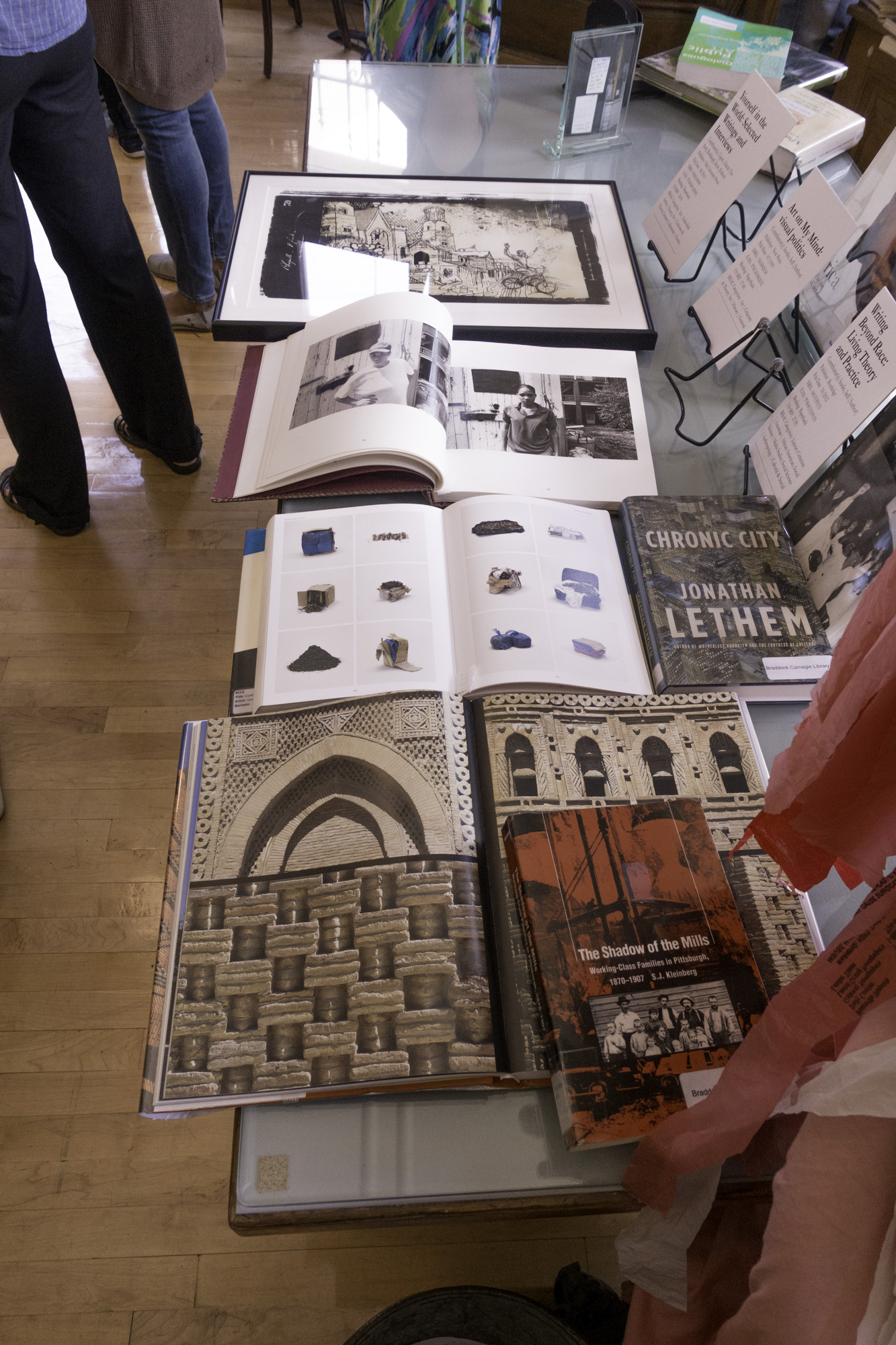

At the Transformazium in Braddock we were given the opportunity to curate small exhibits drawing from multimodal objects around the library. The one above, assembled by Gretchen, Caitlin, and Christiana explored themes of streetscapes, the material life of mud and dirt as it is orchestrated and imagined into ever-larger and more complex brick and mortar superstructures, but also the lives spent within the confines of these walls. Spaces abandoned. Spaces loved. Spaces lost. The ephemerality of built environments as well as the social relations that make and unmake them. Below, Kirk and colleagues assembled a highly textured and tactile array of objects that invited play, wondering, and engagement. This concept of “curation” as offerings or invitations to experience impressed me greatly. It bespeaks a model of art assembly and engagement with multiple publics that is modal, open to change, and acknowledges a wide variety of forms of value. The puppet is no more important, or noble, or significant as an art object than the book. Or the Swoon piece from the art lending library. This, to me, offers a model of art practice that is democratic and rhetorical . The viewers are also makers. Curation serves not as a means of pruning out the worthy from the unworthy but assemblage and invention. The building itself offers this kind of potential: a library formerly serving as the “gift” of culture from the elite to the common folks, but also highly exclusive (along lines of race, class and gender) transformed into a dynamic site for multiple publics.

Treviene Harris

Inside the vitrine is a tortoise shell comb case (Jamaica 1690), with an early rendition of what is still the island of Jamaica’s national coat of arms. The design shows two indigenous people, a man and a woman on either side of a crest adorned with a cross in the middle with five pineapples; a crocodile sits atop the crest and on the bottom the banner translates: “Two Indians shall serve one master.” These words are a sobering reminder of both the enforced servitude and expansiveness of the British colonial empire and that included India, in Asia, and the new “West Indies” of the Americas. After gaining independence from Britain in 1962, Jamaica kept the coat of arms, except the banner now reads: “Out of many, one people.” The image of indigenous people of the Americas on the coat of arms serves to commemorate that the history of the Caribbean, and indeed the Americas, began with indigenous peoples and not the arrival of Europeans.

Photographs by Aaron Henderson unless otherwise noted